By: Eka Margianti Sagimin (A Lecturer at English Department, Universitas Pamulang )

Pidgins and creoles are originally auxiliary languages that developed during sporadic or extended economic and cultural contacts between populations who do not share a common language. Traditional definitions that emerged around 1950 distinguished pidgins from creoles in terms of linguistic complexity and usage. Pidgins were considered rudimentary and linguistically unstable, serving as a second language in restricted sociocultural contexts, while creoles were more developed and stable languages used as a mother tongue by native speakers in various social contexts. The linguistic difference between pidgins and creoles was explained by the language-learning capacity of children born into these new pidgin-speaking communities.

As they grew, these children enriched and complexified the pidgin to meet their communication needs. In this scenario, creole languages developed from pidgin languages as their foundation. Recent definitions now distinguish pidgins and creoles in terms of their function in a linguistic community. Pidgins, whether developed or not, are always secondary languages in a society, used when needed, while creoles are always the primary languages of a community, whether it includes native speakers or not.

Three major debates currently engage creole studies. Firstly, creolists do not all agree on what distinguishes pidgins from creoles, with some emphasizing the linguistic characteristics of these languages, and others focusing on the social conditions that served as the crucible for their genesis and transformation. Another debate concerns the linguistic origins of these languages: do they result from imperfect learning of a target language, causing the grammar of pidgins and creoles to resemble that of the target language? Or do they result from the pragmatic use of the available grammar of speakers (that of their mother tongue) to which they have added a lexicon mainly belonging to another available language?

The third debate concerns the linguistic status of these languages: do pidgins and creoles have a linguistic nature different from that of other languages in the world, justifying their continued distinction by the terms ‘pidgin’ and ‘creole’? Or are they similar to other languages in the world and only differ in their recent history and the social conditions of their genesis? Could the terms ‘pidgin’ and ‘creole’ then only refer to their social history? These questions remain complex within the discipline and reveal the difficulty of defining these languages. In fact, it has become quite common for creolists to refer to them as PC (pidgin/creole), as if they represent a single linguistic phenomenon.

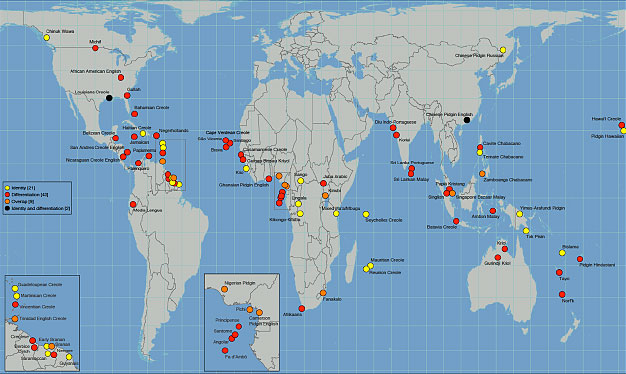

Pidgins and creoles are classified based on three different criteria. The first criterion is the geographical area where they are found: pidgins and creoles from the Caribbean and the Antilles, those from the West African coast, those from the Indian Ocean, and those from Melanesia. The second criterion is the language that has provided the majority of the lexicon, which includes English, French, Spanish, and Portuguese. This results in pidgins and creoles with English-based (Bahamian, Jamaican, Barbadian, Liberian, Hawaiian, etc.), French-based (Martinican, Haitian, Réunionnais, Mauritian, etc.), Spanish-based (Palenquero, Papiamentu, etc.), and Portuguese-based (Cape Verdean, Santomean and Principean, Kristang, etc.).

A small number of pidgins and creoles are grouped into a larger category based on their African, Asian, Austronesian, or Indigenous American roots (Juba Arabic, Lingala, Kituba, Fanakalo, Hiri Motu, Fijian Pidgin, etc.). The final criterion is the social conditions of their genesis, which categorizes them as trade pidgins, fort pidgins, or plantation pidgins and creoles. Using these three criteria, the Solomon Islands Pidgin can be defined as a Melanesian, English-based plantation pidgin. Haitian Creole can be defined as a Caribbean, French-based plantation creole, and the creole of Guinea-Bissau can be defined as an African, Portuguese-based trade creole.

Contact languages have developed wherever different cultural groups have encountered each other without having a common language for communication. The earliest pidgins are no exception to this rule (Holm 2000). Examples of this include the Mediterranean Lingua Franca (attested from 1353) and the Arabic pidgin (attested from the 11th century in Mauritania). With a few exceptions, such as Juba Arabic (spoken in Sudan) and Hiri Motu (spoken in Papua New Guinea), most pidgins and creoles still spoken today originated within the context of European colonization, especially by the English, French, Spanish, and Portuguese, starting from the 16th century.

They are predominantly found in areas where local populations and expansion-seeking Europeans came into contact, driven by territorial expansion and trade for goods: trading posts and former commercial exchange centers (in North America, Africa, and Asia) and former plantation colonies (in the Caribbean, Indian Ocean, and the Pacific) are social contexts that favored the emergence of these new languages.

The development of these languages implies that sporadic commercial and cultural contacts transformed into regular and sustained interactions, allowing communication languages to appear and stabilize. In plantation colonies, these languages developed in association with the often forced movement of populations between different parts of the world, such as through labor contracts and slavery.

Three examples stand out: the transatlantic slave trade that occurred between the African continent and the Caribbean from the mid-16th century to the second half of the 19th century, which enslaved around 11 million people from various parts of West Africa; the population displacement and labor contract system established in the plantations of Mauritius, Seychelles, and Réunion between 1780 and 1910, involving approximately 300,000 individuals; the labor contract system connecting Melanesian islands to Australia between 1864 and 1904, engaging about 62,000 workers.

One might wonder why these population displacements led to the emergence of pidgins and creoles instead of resulting in utilitarian bilingualism. Indeed, each worker could have retained their ancestral language, as first-generation migrants often do in their new country, and learned the dominant language as a second language (both numerically and socially dominant).

Regarding the pidgins and creoles that developed in plantation societies, it is essential to remember that even though demographic and social conditions varied from one plantation to another and from one geographical area to another, in the vast majority of cases, common sociolinguistic characteristics were observed:

- The co-presence of groups of speakers often speaking different, mutually unintelligible languages.

- The absence of a significant language in terms of the number of speakers that could have served as a common language for the workers.

- A significant presence of imported workers (socially dominated) in comparison to the small number of plantation owners and overseers (socially dominant) living on the plantations.

- Working and living conditions that did not allow for sustained, extensive, and regular contact with the socially dominant language, which could have facilitated learning. In such conditions, it was nearly impossible for the workers to acquire this language, except for the available lexicon in the form of words regularly heard during work-related activities, which were recognized and easily learned.

Some researchers believe that beyond the purely instrumental aspect, the genesis of creoles is part of a process of linguistic resistance against the hegemony that existed in these socioeconomic environments.

The genesis of the oldest pidgins and creoles (those of the Atlantic) has left few written traces, with some well-documented exceptions, such as Sranan, spoken in Suriname. The development of more recent pidgins (those of the Pacific in the 19th century) has been the subject of documentation, although sometimes partial and often inaccurate. This documentation allows for a better understanding of the interplay between the social and linguistic dimensions that led to their genesis and transformation. Nevertheless, several linguistic theories have been proposed to explain their origin.

Some, known as superstratist theories, emphasize the role of European languages in the genesis of these languages. Two notable theories in this category are the theory of the European dialect (advocated by Robert Chaudenson 2003) and the theory of imperfect acquisition of the target language (explained by Jeff Siegel 2008, among others).

Others, classified as substratist theories, emphasize the significant role of the workers’ languages in this linguistic reconfiguration. The theory of relexification, demonstrated by Claire Lefebvre (Lefebvre 1986), and the calque theory (defended by Roger Keesing 1988) are the most developed in this category.

It is highly likely that many pidgins and creoles have disappeared without leaving a trace, especially when the contacts that gave rise to them ceased. Those that exist today have undergone significant transformations, much like other languages in the world. Some have become the national languages of the countries where they are spoken today, often in parallel with the language of the former colonial power. In some countries, such as Haiti, for example, the creole is used as the medium of instruction in schools. In other places, the ex-colonial language has often become the official language of the postcolonial nation, as well as the language of education, while the creole or pidgin is relegated to a vernacular role.

The cultural legitimacy enjoyed by a pidgin or creole as the vernacular language of the local population does not always translate into linguistic legitimacy. Sometimes, a lingering influence of colonial linguistic ideology prevails, leading some speakers to consider the pidgin or creole they speak as not a “real” language. As a result, they resist its inclusion in the school curriculum.

The diversification that is a normal part of the language transformation process also affects pidgins and creoles. Alongside regional dialects that emerged early on, sociolects have developed, connoting the socio-economic status and educational level of speakers, and in some cases, their familiarity with the former colonial language.