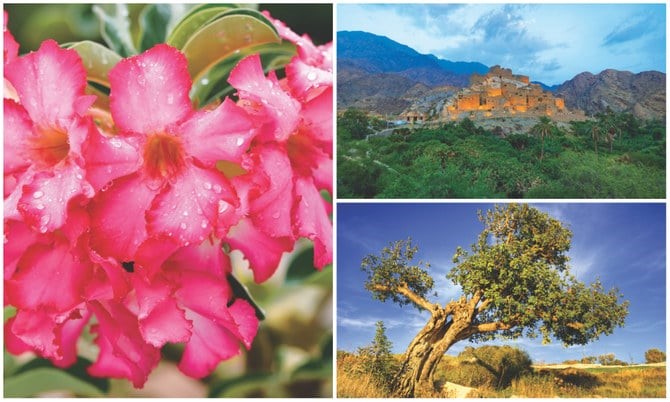

JEDDAH: Although desert covers the majority of Saudi Arabia’s land, a surprising variety of indigenous plant species can tolerate the harsh climate. Efforts are now ongoing, under the auspices of the Saudi Green Initiative, to preserve and even enhance the amount of greenery across the Kingdom.

The Kingdom is home to a plethora of greenery, including over 2,000 wild plant species belonging to 142 groups, from its desert vistas in the north to the southern region of Asir. However, according to the Saudi National Center for Wildlife, approximately 600 of these species are endangered, and 21 are already presumed to be extinct.

The SGI, launched in March 2021, is the country’s greatest afforestation project to date, with a goal of planting 450 million trees by 2030. By the end of 2021, around 10 million trees had been planted across all 13 areas of the Kingdom.

Forests may not be the first sort of habitat that comes to mind when one thinks about Saudi Arabia. The Kingdom does, however, have over 2.7 million hectares of woods, primarily in the inaccessible southwestern highlands of Abha and Asir.

On the surface, the objective of planting 450 million trees, let alone the projected greening of the desert, seemed daunting, especially given the Kingdom’s frantic urban expansion.

To counteract the potential effects of urban sprawl, the Saudi government has established specific SGI goals to integrate green spaces seamlessly into urban expansion, including as parkland and afforestation within the Kingdom’s desert cities.

Greening uncontrolled surfaces in these cities would not only help to reduce rising temperatures, but will also reduce carbon dioxide emissions, enhance air quality, create possibilities for more active lifestyles, and beautify cities in a sustainable manner.

Meanwhile, in more rural areas, greening efforts must contend with increasing deserts, limited water resources, and record-high temperatures, all of which are assumed to be the outcome of human-caused climate change.

The SGI road map aims to halt and reverse desertification and soil degradation, protect the Kingdom’s unique biodiversity, and conserve limited water resources in a country where rainfall is rare and groundwater is depleting.

Saudi Arabia now includes 15 biodiversity-protected sites, 12 of which are on land and three of which are marine. According to the National Center for Wildlife, that number should be increased to 75, with 62 on land and 13 in coastal and marine areas.

The King Salman Royal Nature Reserve in northern Saudi Arabia accounts for approximately 6% of the Kingdom’s total land area. It has mountain topography, huge plains, and high plateaus, as well as 300 animal species and rare archaeological heritage sites going back to 8,000 BC.

The reserve’s administration plans to plant 3.1 million trees by 2027 in order to improve the resilience and diversity of this valuable natural ecosystem.

“We are devoted to boosting vegetation cover, as we have previously accomplished by planting 600,000 plants and conducting numerous seed-sowing programs to increase vegetation in the reserve,” a KSRNR spokeswoman told Arab News.

“The trees and shrubs are perennial species that help to rebuild arid ecosystems.” These plants are endemic to desert ecosystems and have evolved to the extreme circumstances of the desert, such as drought and high temperatures, and do not require a lot of water for irrigation.

“The strategic goal of the reserve is to build a seedling program that involves several projects, such as the installation of the main nursery.”

Nonetheless, water continues to be a major barrier for conservation efforts and greening initiatives in the Kingdom. Over the millennia, Arabian Peninsula residents discovered means to sustain life and endure droughts by digging freshwater wells. Following the Kingdom’s economic development in the 1970s, Saudis gradually shifted to modern farming methods, increasingly relying on groundwater reserves.

With no rivers or natural lakes to replenish supplies and very little yearly rainfall, Saudi Arabia constructed saltwater desalination plants on its eastern and western coasts to serve inland towns. Nonetheless, demand for freshwater is increasing, and natural aquifers are rapidly disappearing.

As a result, the Saudi government is looking at ways to maintain its water supplies and use them more efficiently in order to meet the demands of a booming economy while still keeping green spaces well watered.

According to Maria Nava, a scientific consultant for Greening Arabia at the King Abdullah University of Science and Technology Center for Desert Agriculture, the SGI’s strategic team is expected to irrigate newly planted vegetation with treated effluent.

Another goal, she stated, is “to reduce rainfall loss to the sea or through sand penetration in the Kingdom through the introduction and upgrading of water harvesting and soil remediation for water retention where needed.”

Plants in metropolitan environments require substantially more water and canopy cover to create shade than those in mountain, wadi, and desert climates, according to Nava.

“This vegetation demands more water than desert trees, which are drought-resistant and have fewer leaves,” she continues.

Source: Arab News